Abstract(post of Nov.17)The Glamour of the Goldern Era of Hollywood- Glamour is experienced mainly through visual ephemera.

- Its appeal was most powerful to those who lay outside the realm of privilege and success

- Up until the 1960s, magazines and photographers worked off real social environments After the collapse of formal high society, and the demise of the well-bred or debutante model, it was the iconic images of the past that provided the most potent source of inspiration. Contemporary glamour is itself derivative; self-generating and self-referential.

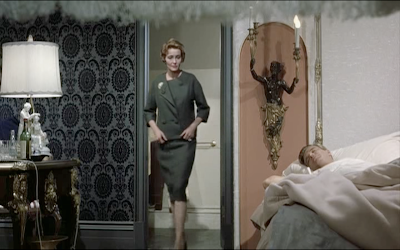

Introduction to 3 movies"To Catch a Thief", "La Dolce Vita", and "Breakfast at Tiffany's"

Siting (the Milieux) -a mapping out of all the locations of each of the 3 films (hotels, shops, driving routes, vistas, districts)

- The urban scene was one in which the rich and fashionable were constantly seeking to establish exlucsivity in a context in which public places and commercial institutions, to some degree, were open

- Certain areas acquired an aura of desirability through the presence of the rich, their patterns of competition and display, and the institutions of consumption and entertaiment.

-The commercial and entertainment establishments that sprang up within these areas were crucial tools of reinformcement and diffusion of this image. With the rapid development of the commercial sector, shops and stores came to occupy an increasingly important place in the visual and sensory experience of the metropolitan life.

-global retail areas – urban public spaces (brand zones; city as “added value”; omotesando jewel boxes)

-In the history of glamour, cities are always important. The very idea of the modern city is bound up with wealth, power, beauty, and publicity. To exist, it requires a high degree of urbanization, the social and physical mobility of capitalist society, some sense of equality and citizenship, and a distinctive bourgeois mentality.

-monetarily-propelled public spaces (& social interaction); connected “family tree”

-genius loci of the late capitalist city

a. window display, lighting

b. dimensions, ratios

c. s, m, l, xl (tag, bag, rack, shelf, boutique..)

-look up Tschumi, Veblen, Walter Benjamin, Foucault

Clothing (the Skin) -the role of couture (in each film); criteria of couture….influence of cinema and vice versa

Paparazzi (the Dogs) -on and offscreen lives of the stars (how architecture hides and emphasizes gossip)

Objects (the Things) -the objects of desire; curiosity cabinet; not an encyclopedia; curation,

-what criteria denote luxury status (“gemstones to jewelery” Roland Barthes; detail, taste, distinction)

-modern day, links to business, sale environment pyramids

-faith, transcendence, ecstacy, myth, sacrifice, ritual, community, identity

-luxury item as new ecclesiastical relic (church built around unique article)

-litany, pilgrimage, rite of passage (shopping)

-icons and ads (the immaterial world created around the object)

-look up Bourdieu (Luxury is the fetishization of this condition; necessary for sense of identity; “sign-value”), Baudrillard, John Berger, Kingwell